Desde los primeros registros de la historia surge la necesidad de preservar un conocimiento, una experiencia que, de alguna forma, favorece la continuación de la especie; desde las primeras pinturas rupestres, pasando por las tablillas y rollos de papiro y pergamino, nos encontramos con mensajes que se consideran importantes, fundamentales y fundacionales, y buscan ser recordados y considerados, preservados para las futuras generaciones, por lo que supone una parte natural del proceso evolutivo de la humanidad construir espacios que permitan resguardar tal material, de esta forma, se crearon las bibliotecas, aunque en ese entonces no se llamaban así.

En la antigüedad las bibliotecas crecían al amparo de un palacio real, un templo o la casa particular de un rico mecenas, aunque tanto en oriente como occidente, las más comunes eran las segundas, ya que santuarios y abadías eran los lugares comunes de encuentro e investigación para letrados y estudiosos, escribas y copistas. La primera biblioteca cuya existencia se registra es la de Asurbanipal, nombrada en honor al rey asirio, que gobernó a mediados del 600 AC, aunque fue creada por varios gobernantes anteriores, edificada en lo que hoy es Irak, en una ciudad cerca del río Tigris.

Babilonia, Kalhu, Sippar y Uruk tenían famosas bibliotecas en sus templos, siendo la primera la que mayor notoriedad ganó después de la conquista de Alejandro Magno, al convertirse en la biblioteca Alejandrina, casi un mito del mundo antiguo, reconocida como las más grande biblioteca de aquel tiempo, siglo 2 AC. En estos recintos se preservaban obras que versaban sobre las más diversas temáticas: rituales, doctrinas religiosas, encantamientos, oraciones y rezos para exorcizar, descubrimientos científicos, matemáticas, astronomía, medicina, así como lectura e interpretación de augurios.

Amoxcalli es el nombre que los Mexicas le daban a sus “casas del libro”, las que fueron totalmente destruidas por la conquista europea, porque es necesario reconocer el rol fundamental que tienen las bibliotecas y su afán conservador en la construcción de los imperios, ya que sus criterios de preservación sólo incluyen a obras y autores universales de su propia cultura, en este sentido, cada conquista significa la destrucción de una biblioteca con un acervo cultural que no se reconoce y que pasa al sustrato de la sociedad. Este avance imperial persiste hasta hoy en el que vemos cómo, a pesar de celebrar un día de la lengua materna, se persigue y elimina a quienes quieren preservar sus idiomas y toda la historia, creencias y costumbres en las que se sostiene.

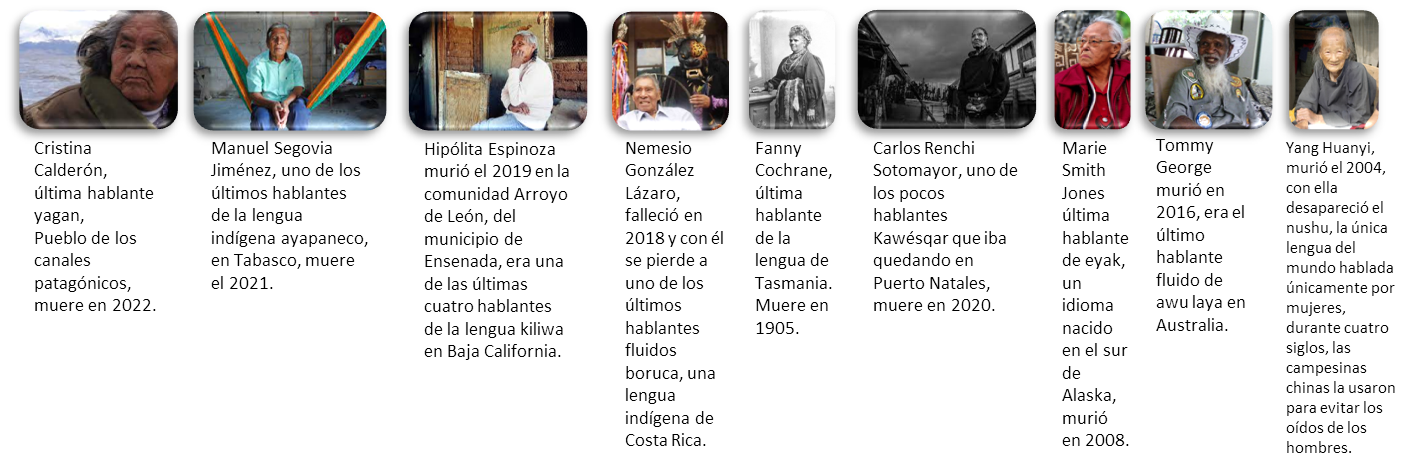

Entre el año 2006 y 2016, un lapso de 10 años, más de 100 lenguas desaparecieron, ya en 1905 moría la última hablante de la lengua nativa de Tasmania, Fanny Cochrane; el 29 de julio de 2016 murió Tommy George, el último hablante de Awu Laya, una lengua aborigen australiana con más de 42000 años de historia y saberes transmitidos oralmente por los kuku-thaypan. En noviembre de ese mismo año fue asesinada en las selvas del norte de Perú, Rosa Andrade, la última mujer hablante de Resígaro, una de las 43 lenguas indígenas de la Amazonía. Hace pocos días falleció Cristina Calderón, última hablante del Yagán de las pocas sobrevivientes del genocidio de los pueblos patagónicos. Cada dos semanas muere una lengua y de mantenerse este ritmo de extinción puede que al finalizar este siglo más de las 7000 lenguas que se hablan hoy, desaparezcan y no habrá biblioteca que nos salve de esa pérdida.

From the first records of history arises the need to preserve knowledge, an experience that, in some way, favors the continuation of the species; from the first cave paintings, through the tablets and rolls of papyrus and parchment, we find messages that are considered important, fundamental and foundational, and seek to be remembered and considered, preserved for future generations, for what is a natural part of the evolutionary process of humanity to build spaces that allow safeguarding such material, in this way, libraries were created, although at that time they were not called that.

In ancient times, libraries grew under the protection of a royal palace, a temple or the private house of a rich patron, although both in East and West, the most common were the second, since sanctuaries and abbeys were the common places of meeting and research for bookman and scholars, scribes and copyists. The first library whose existence is recorded is that of Ashurbanipal, named after the Assyrian king, who ruled in mid-600 BC, although it was created by several previous rulers, built in what is now Iraq, in a city near the Tigris River.

Babylon, Kalhu, Sippar and Uruk had famous libraries in their temples, the first being the one that gained the most notoriety after the conquest of Alexander the Great, by becoming the Alexandrian library, almost a myth of the ancient world, recognized as the largest library of that time, 2nd century BC. In these enclosures, works were preserved that dealt with the most diverse themes: rituals, religious doctrines, enchantments, orisons and prayers to exorcise, scientific discoveries, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, as well as reading and interpretation of omens.

Amoxcalli is the name that the Mexicas gave to their «book houses», which were totally destroyed by the European conquest, because it is necessary to recognize the fundamental role that libraries and their conservative desire have in the construction of empires, since that their preservation criteria only include works and universal authors of their own culture, in this sense, each conquest means the destruction of a library with a cultural heritage that is not recognized and that passes to the substratum of society. This imperial advance persists until today in which we see how, despite celebrating a day of the mother tongue, those who want to preserve their languages and all the history, beliefs and customs on which they are sustained are persecuted and eliminated.

Between 2006 and 2016, a period of 10 years, more than 100 languages disappeared, already in 1905 the last speaker of the native language of Tasmania, Fanny Cochrane, died; On July 29, 2016, Tommy George died, the last speaker of Awu Laya, an Australian aboriginal language with more than 42,000 years of history and knowledge transmitted orally by the Kuku-thaypan. In November of that same year, Rosa Andrade, the last woman who spoke Resígaro, one of the 43 indigenous languages of the Amazon, was murdered in the jungles of northern Peru. A few days ago, Cristina Calderón passed away, the last Yagán speaker among the few survivors of the genocide of the Patagonian peoples. Every two weeks a language dies and if this rate of extinction continues it may be that by the end of this century more than the 7000 languages spoken today will disappear and there will be no library to save us from that loss.